In this article we will consider basic operations on points in Euclidean space which maintains the foundation of the whole analytical geometry. We will consider for each point $\mathbf r$ the vector $\vec{\mathbf r}$ directed from $\mathbf 0$ to $\mathbf r$. Later we will not distinguish between $\mathbf r$ and $\vec{\mathbf r}$ and use the term point as a synonym for vector.

Linear operations

Both 2D and 3D points maintain linear space, which means that for them sum of points and multiplication of point by some number are defined. Here are those basic implementations for 2D:

struct point2d {

ftype x, y;

point2d() {}

point2d(ftype x, ftype y): x(x), y(y) {}

point2d& operator+=(const point2d &t) {

x += t.x;

y += t.y;

return *this;

}

point2d& operator-=(const point2d &t) {

x -= t.x;

y -= t.y;

return *this;

}

point2d& operator*=(ftype t) {

x *= t;

y *= t;

return *this;

}

point2d& operator/=(ftype t) {

x /= t;

y /= t;

return *this;

}

point2d operator+(const point2d &t) const {

return point2d(*this) += t;

}

point2d operator-(const point2d &t) const {

return point2d(*this) -= t;

}

point2d operator*(ftype t) const {

return point2d(*this) *= t;

}

point2d operator/(ftype t) const {

return point2d(*this) /= t;

}

};

point2d operator*(ftype a, point2d b) {

return b * a;

}

And 3D points:

struct point3d {

ftype x, y, z;

point3d() {}

point3d(ftype x, ftype y, ftype z): x(x), y(y), z(z) {}

point3d& operator+=(const point3d &t) {

x += t.x;

y += t.y;

z += t.z;

return *this;

}

point3d& operator-=(const point3d &t) {

x -= t.x;

y -= t.y;

z -= t.z;

return *this;

}

point3d& operator*=(ftype t) {

x *= t;

y *= t;

z *= t;

return *this;

}

point3d& operator/=(ftype t) {

x /= t;

y /= t;

z /= t;

return *this;

}

point3d operator+(const point3d &t) const {

return point3d(*this) += t;

}

point3d operator-(const point3d &t) const {

return point3d(*this) -= t;

}

point3d operator*(ftype t) const {

return point3d(*this) *= t;

}

point3d operator/(ftype t) const {

return point3d(*this) /= t;

}

};

point3d operator*(ftype a, point3d b) {

return b * a;

}

Here ftype is some type used for coordinates, usually int, double or long long.

Dot product

Definition

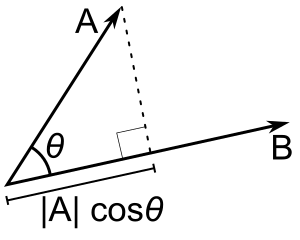

The dot (or scalar) product $\mathbf a \cdot \mathbf b$ for vectors $\mathbf a$ and $\mathbf b$ can be defined in two identical ways. Geometrically it is product of the length of the first vector by the length of the projection of the second vector onto the first one. As you may see from the image below this projection is nothing but $|\mathbf a| \cos \theta$ where $\theta$ is the angle between $\mathbf a$ and $\mathbf b$. Thus $\mathbf a\cdot \mathbf b = |\mathbf a| \cos \theta \cdot |\mathbf b|$.

The dot product holds some notable properties:

- $\mathbf a \cdot \mathbf b = \mathbf b \cdot \mathbf a$

- $(\alpha \cdot \mathbf a)\cdot \mathbf b = \alpha \cdot (\mathbf a \cdot \mathbf b)$

- $(\mathbf a + \mathbf b)\cdot \mathbf c = \mathbf a \cdot \mathbf c + \mathbf b \cdot \mathbf c$

I.e. it is a commutative function which is linear with respect to both arguments. Let’s denote the unit vectors as \[\mathbf e_x = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\\ 0 \\\ 0 \end{pmatrix}, \mathbf e_y = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\\ 1 \\\ 0 \end{pmatrix}, \mathbf e_z = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\\ 0 \\\ 1 \end{pmatrix}.\]

With this notation we can write the vector $\mathbf r = (x;y;z)$ as $r = x \cdot \mathbf e_x + y \cdot \mathbf e_y + z \cdot \mathbf e_z$. And since for unit vectors \(\mathbf e_x\cdot \mathbf e_x = \mathbf e_y\cdot \mathbf e_y = \mathbf e_z\cdot \mathbf e_z = 1,\\\ \mathbf e_x\cdot \mathbf e_y = \mathbf e_y\cdot \mathbf e_z = \mathbf e_z\cdot \mathbf e_x = 0\) we can see that in terms of coordinates for $\mathbf a = (x_1;y_1;z_1)$ and $\mathbf b = (x_2;y_2;z_2)$ holds \[\mathbf a\cdot \mathbf b = (x_1 \cdot \mathbf e_x + y_1 \cdot\mathbf e_y + z_1 \cdot\mathbf e_z)\cdot( x_2 \cdot\mathbf e_x + y_2 \cdot\mathbf e_y + z_2 \cdot\mathbf e_z) = x_1 x_2 + y_1 y_2 + z_1 z_2\]

That is also the algebraic definition of the dot product. From this we can write functions which calculate it.

ftype dot(point2d a, point2d b) {

return a.x * b.x + a.y * b.y;

}

ftype dot(point3d a, point3d b) {

return a.x * b.x + a.y * b.y + a.z * b.z;

}

When solving problems one should use algebraic definition to calculate dot products, but keep in mind geometric definition and properties to use it.

Properties

We can define many geometrical properties via the dot product. For example

- Norm of $\mathbf a$ (squared length): $|\mathbf a|^2 = \mathbf a\cdot \mathbf a$

- Length of $\mathbf a$: $|\mathbf a| = \sqrt{\mathbf a\cdot \mathbf a}$

- Projection of $\mathbf a$ onto $\mathbf b$: $\dfrac{\mathbf a\cdot\mathbf b}{|\mathbf b|}$

- Angle between vectors: $\arccos \left(\dfrac{\mathbf a\cdot \mathbf b}{|\mathbf a| \cdot |\mathbf b|}\right)$

- From the previous point we may see that the dot product is positive if the angle between them is acute, negative if it is obtuse and it equals zero if they are orthogonal, i.e. they form a right angle.

Note that all these functions do not depend on the number of dimensions, hence they will be the same for the 2D and 3D case:

ftype norm(point2d a) {

return dot(a, a);

}

double abs(point2d a) {

return sqrt(norm(a));

}

double proj(point2d a, point2d b) {

return dot(a, b) / abs(b);

}

double angle(point2d a, point2d b) {

return acos(dot(a, b) / abs(a) / abs(b));

}

To see the next important property we should take a look at the set of points $\mathbf r$ for which $\mathbf r\cdot \mathbf a = C$ for some fixed constant $C$. You can see that this set of points is exactly the set of points for which the projection onto $\mathbf a$ is the point $C \cdot \dfrac{\mathbf a}{|\mathbf a|}$ and they form a hyperplane orthogonal to $\mathbf a$. You can see the vector $\mathbf a$ alongside with several such vectors having same dot product with it in 2D on the picture below:

In 2D these vectors will form a line, in 3D they will form a plane. Note that this result allows us to define a line in 2D as $\mathbf r\cdot \mathbf n=C$ or $(\mathbf r - \mathbf r_0)\cdot \mathbf n=0$ where $\mathbf n$ is vector orthogonal to the line and $\mathbf r_0$ is any vector already present on the line and $C = \mathbf r_0\cdot \mathbf n$. In the same manner a plane can be defined in 3D.

Cross product

Definition

Assume you have three vectors $\mathbf a$, $\mathbf b$ and $\mathbf c$ in 3D space joined in a parallelepiped as in the picture below:

How would you calculate its volume? From school we know that we should multiply the area of the base with the height, which is projection of $\mathbf a$ onto direction orthogonal to base. That means that if we define $\mathbf b \times \mathbf c$ as the vector which is orthogonal to both $\mathbf b$ and $\mathbf c$ and which length is equal to the area of the parallelogram formed by $\mathbf b$ and $\mathbf c$ then $|\mathbf a\cdot (\mathbf b\times\mathbf c)|$ will be equal to the volume of the parallelepiped. For integrity we will say that $\mathbf b\times \mathbf c$ will be always directed in such way that the rotation from the vector $\mathbf b$ to the vector $\mathbf c$ from the point of $\mathbf b\times \mathbf c$ is always counter-clockwise (see the picture below).

This defines the cross (or vector) product $\mathbf b\times \mathbf c$ of the vectors $\mathbf b$ and $\mathbf c$ and the triple product $\mathbf a\cdot(\mathbf b\times \mathbf c)$ of the vectors $\mathbf a$, $\mathbf b$ and $\mathbf c$.

Some notable properties of cross and triple products:

- $\mathbf a\times \mathbf b = -\mathbf b\times \mathbf a$

- $(\alpha \cdot \mathbf a)\times \mathbf b = \alpha \cdot (\mathbf a\times \mathbf b)$

- For any $\mathbf b$ and $\mathbf c$ there is exactly one vector $\mathbf r$ such that $\mathbf a\cdot (\mathbf b\times \mathbf c) = \mathbf a\cdot\mathbf r$ for any vector $\mathbf a$.

Indeed if there are two such vectors $\mathbf r_1$ and $\mathbf r_2$ then $\mathbf a\cdot (\mathbf r_1 - \mathbf r_2)=0$ for all vectors $\mathbf a$ which is possible only when $\mathbf r_1 = \mathbf r_2$. - $\mathbf a\cdot (\mathbf b\times \mathbf c) = \mathbf b\cdot (\mathbf c\times \mathbf a) = -\mathbf a\cdot( \mathbf c\times \mathbf b)$

- $(\mathbf a + \mathbf b)\times \mathbf c = \mathbf a\times \mathbf c + \mathbf b\times \mathbf c$. Indeed for all vectors $\mathbf r$ the chain of equations holds:

Which proves $(\mathbf a + \mathbf b)\times \mathbf c = \mathbf a\times \mathbf c + \mathbf b\times \mathbf c$ due to point 3.

- $|\mathbf a\times \mathbf b|=|\mathbf a| \cdot |\mathbf b| \sin \theta$ where $\theta$ is angle between $\mathbf a$ and $\mathbf b$, since $|\mathbf a\times \mathbf b|$ equals to the area of the parallelogram formed by $\mathbf a$ and $\mathbf b$.

Given all this and that the following equation holds for the unit vectors \(\mathbf e_x\times \mathbf e_x = \mathbf e_y\times \mathbf e_y = \mathbf e_z\times \mathbf e_z = \mathbf 0,\\\ \mathbf e_x\times \mathbf e_y = \mathbf e_z,~\mathbf e_y\times \mathbf e_z = \mathbf e_x,~\mathbf e_z\times \mathbf e_x = \mathbf e_y\) we can calculate the cross product of $\mathbf a = (x_1;y_1;z_1)$ and $\mathbf b = (x_2;y_2;z_2)$ in coordinate form: \[\mathbf a\times \mathbf b = (x_1 \cdot \mathbf e_x + y_1 \cdot \mathbf e_y + z_1 \cdot \mathbf e_z)\times (x_2 \cdot \mathbf e_x + y_2 \cdot \mathbf e_y + z_2 \cdot \mathbf e_z) =\] \[(y_1 z_2 - z_1 y_2)\mathbf e_x + (z_1 x_2 - x_1 z_2)\mathbf e_y + (x_1 y_2 - y_1 x_2)\]

Which also can be written in the more elegant form: \[\mathbf a\times \mathbf b = \begin{vmatrix}\mathbf e_x & \mathbf e_y & \mathbf e_z \\\ x_1 & y_1 & z_1 \\\ x_2 & y_2 & z_2 \end{vmatrix},~a\cdot(b\times c) = \begin{vmatrix} x_1 & y_1 & z_1 \\\ x_2 & y_2 & z_2 \\\ x_3 & y_3 & z_3 \end{vmatrix}\]

Here $| \cdot |$ stands for the determinant of a matrix.

Some kind of cross product (namely the pseudo-scalar product) can also be implemented in the 2D case. If we would like to calculate the area of parallelogram formed by vectors $\mathbf a$ and $\mathbf b$ we would compute $|\mathbf e_z\cdot(\mathbf a\times \mathbf b)| = |x_1 y_2 - y_1 x_2|$. Another way to obtain the same result is to multiply $|\mathbf a|$ (base of parallelogram) with the height, which is the projection of vector $\mathbf b$ onto vector $\mathbf a$ rotated by $90^\circ$ which in turn is $\widehat{\mathbf a}=(-y_1;x_1)$. That is, to calculate $|\widehat{\mathbf a}\cdot\mathbf b|=|x_1y_2 - y_1 x_2|$.

If we will take the sign into consideration then the area will be positive if the rotation from $\mathbf a$ to $\mathbf b$ (i.e. from the view of the point of $\mathbf e_z$) is performed counter-clockwise and negative otherwise. That defines the pseudo-scalar product. Note that it also equals $|\mathbf a| \cdot |\mathbf b| \sin \theta$ where $\theta$ is angle from $\mathbf a$ to $\mathbf b$ count counter-clockwise (and negative if rotation is clockwise).

Let’s implement all this stuff!

point3d cross(point3d a, point3d b) {

return point3d(a.y * b.z - a.z * b.y,

a.z * b.x - a.x * b.z,

a.x * b.y - a.y * b.x);

}

ftype triple(point3d a, point3d b, point3d c) {

return dot(a, cross(b, c));

}

ftype cross(point2d a, point2d b) {

return a.x * b.y - a.y * b.x;

}

Properties

As for the cross product, it equals to the zero vector iff the vectors $\mathbf a$ and $\mathbf b$ are collinear (they form a common line, i.e. they are parallel). The same thing holds for the triple product, it is equal to zero iff the vectors $\mathbf a$, $\mathbf b$ and $\mathbf c$ are coplanar (they form a common plane).

From this we can obtain universal equations defining lines and planes. A line can be defined via its direction vector $\mathbf d$ and an initial point $\mathbf r_0$ or by two points $\mathbf a$ and $\mathbf b$. It is defined as $(\mathbf r - \mathbf r_0)\times\mathbf d=0$ or as $(\mathbf r - \mathbf a)\times (\mathbf b - \mathbf a) = 0$. As for planes, it can be defined by three points $\mathbf a$, $\mathbf b$ and $\mathbf c$ as $(\mathbf r - \mathbf a)\cdot((\mathbf b - \mathbf a)\times (\mathbf c - \mathbf a))=0$ or by initial point $\mathbf r_0$ and two direction vectors lying in this plane $\mathbf d_1$ and $\mathbf d_2$: $(\mathbf r - \mathbf r_0)\cdot(\mathbf d_1\times \mathbf d_2)=0$.

In 2D the pseudo-scalar product also may be used to check the orientation between two vectors because it is positive if the rotation from the first to the second vector is clockwise and negative otherwise. And, of course, it can be used to calculate areas of polygons, which is described in a different article. A triple product can be used for the same purpose in 3D space.

Exercises

Line intersection

There are many possible ways to define a line in 2D and you shouldn’t hesitate to combine them. For example we have two lines and we want to find their intersection points. We can say that all points from first line can be parameterized as $\mathbf r = \mathbf a_1 + t \cdot \mathbf d_1$ where $\mathbf a_1$ is initial point, $\mathbf d_1$ is direction and $t$ is some real parameter. As for second line all its points must satisfy $(\mathbf r - \mathbf a_2)\times \mathbf d_2=0$. From this we can easily find parameter $t$: \[(\mathbf a_1 + t \cdot \mathbf d_1 - \mathbf a_2)\times \mathbf d_2=0 \quad\Rightarrow\quad t = \dfrac{(\mathbf a_2 - \mathbf a_1)\times\mathbf d_2}{\mathbf d_1\times \mathbf d_2}\]

Let’s implement function to intersect two lines.

point2d intersect(point2d a1, point2d d1, point2d a2, point2d d2) {

return a1 + cross(a2 - a1, d2) / cross(d1, d2) * d1;

}

Planes intersection

However sometimes it might be hard to use some geometric insights. For example, you’re given three planes defined by initial points $\mathbf a_i$ and directions $\mathbf d_i$ and you want to find their intersection point. You may note that you just have to solve the system of equations: \[\begin{cases}\mathbf r\cdot \mathbf n_1 = \mathbf a_1\cdot \mathbf n_1, \\\ \mathbf r\cdot \mathbf n_2 = \mathbf a_2\cdot \mathbf n_2, \\\ \mathbf r\cdot \mathbf n_3 = \mathbf a_3\cdot \mathbf n_3\end{cases}\]

Instead of thinking on geometric approach, you can work out an algebraic one which can be obtained immediately. For example, given that you already implemented a point class, it will be easy for you to solve this system using Cramer’s rule because the triple product is simply the determinant of the matrix obtained from the vectors being its columns:

point3d intersect(point3d a1, point3d n1, point3d a2, point3d n2, point3d a3, point3d n3) {

point3d x(n1.x, n2.x, n3.x);

point3d y(n1.y, n2.y, n3.y);

point3d z(n1.z, n2.z, n3.z);

point3d d(dot(a1, n1), dot(a2, n2), dot(a3, n3));

return point3d(triple(d, y, z),

triple(x, d, z),

triple(x, y, d)) / triple(n1, n2, n3);

}

Now you may try to find out approaches for common geometric operations yourself to get used to all this stuff.